BY LOUIS J. FREEH

Sunday, June 25, 2006 12:01 a.m. EDT

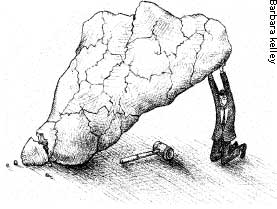

Ten years ago today, acting under direct orders from senior Iranian

government leaders, the Saudi Hezbollah detonated a 25,000-pound TNT bomb that

killed 19 U.S. airmen in their dormitory at Khobar Towers in Dhahran, Saudi

Arabia. The blast wave destroyed Building 131 and grievously wounded hundreds of

additional Air Force personnel. It also killed an unknown number of Saudi

civilians in a nearby park.

The 19 Americans murdered were members of the 4,404th Wing, who were risking

their lives to enforce the no-fly zone over southern Iraq. This was a

U.N.-mandated mission after the 1991 Gulf War to stop Saddam Hussein from

killing his Shiite people. The Khobar victims, along with the courageous

families and friends who mourn them this weekend in Washington, deserve our

respect and honor. More importantly, they must be remembered, because American

justice has still been denied.

Although a federal grand jury handed up indictments in June 2001--days before

I left as FBI director and a week before some of the charges against 14 of the

terrorists would have lapsed because of the statute of limitations--two of the

primary leaders of the attack, Ahmed Ibrahim al-Mughassil and Abdel Hussein

Mohamed al-Nasser, are living comfortably in Iran with about as much to fear

from America as Osama bin Laden had prior to Sept. 11 (to wit, U.S.

marshals showing up to serve warrants for their arrests).

| The aftermath of the Khobar bombing

is just one example of how successive U.S. governments have mishandled Iran. On

June 25, 1996, President Clinton declared that "no stone would be left

unturned" to find the bombers and bring them to "justice." Within

hours, teams of FBI agents, and forensic and technical personnel, were en route

to Khobar. The president told the Saudis and the 19 victims' families that I was

responsible for the case. This assignment became very personal and solemn for

me, as it meant that I was the one who dealt directly with the victims'

survivors. These disciplined military families asked only one thing of me and

their country: "Please find out who did this to our sons, husbands,

brothers and fathers and bring them to justice."

|

|

It soon became clear that Mr. Clinton and his national security adviser,

Sandy Berger, had no interest in confronting the fact that Iran had blown up the

towers. This is astounding, considering that the Saudi Security Service had

arrested six of the bombers after the attack. As FBI agents sifted through the

remains of Building 131 in 115-degree heat, the bombers admitted they had been

trained by the Iranian external security service (IRGC) in Lebanon's Beka Valley

and received their passports at the Iranian Embassy in Damascus, Syria, along

with $250,000 cash for the operation from IRGC Gen. Ahmad Sharifi.

We later learned that senior members of the Iranian government, including

Ministry of Defense, Ministry of Intelligence and Security and the Spiritual

Leader's office had selected Khobar as their target and commissioned the Saudi

Hezbollah to carry out the operation. The Saudi police told us that FBI agents

had to interview the bombers in custody in order to make our case. To make this

happen, however, the U.S. president would need to make a personal request to

Saudi Crown Prince Abdullah.

So for 30 months, I wrote and rewrote the same set of simple talking points

for the president, Mr. Berger, and others to press the FBI's request to go

inside a Saudi prison and interview the Khobar bombers. And for 30 months

nothing happened. The Saudis reported back to us that the president and Mr.

Berger would either fail to raise the matter with the crown prince or raise it

without making any request. On one such occasion, our commander in chief instead

hit up Prince Abdullah for a contribution to his library. Mr. Berger never once,

in the course of the five-year investigation which coincided with his tenure,

even asked how the investigation was going.

In their only bungled attempt to support the FBI, a letter from the president

intended for Iran's President Mohammad Khatami, asking for "help" on

the Khobar case, was sent to the Omanis, who had direct access to Mr. Khatami.

This was done without advising either the FBI or the Saudis who were exposed in

the letter as providing help to the Americans. We only found out about the

letter because it was misdelivered to the spiritual leader, Ayatollah Ali

Khamenei, who then publicly denounced the U.S. This was an embarrassment for the

Saudis who had been fully cooperating with the FBI by providing direct evidence

of Iranian involvement. Both Saudi Prince Bandar and Interior Minister Prince

Nayef, who had put themselves and their government at great risk to help the

FBI, were now undermined by America's president.

The Clinton administration was set on "improving" relations with

what it mistakenly perceived to be a moderate Iranian president. But it also

wanted to accrue the political mileage of proclaiming to the world, and to the

19 survivor families, that America was aggressively pursuing the bombers. When I

would tell Mr. Berger that we could close the investigation if it compromised

the president's foreign policy, the answer was always: "Leave no stone

unturned."

Meanwhile, then-Secretary of State Madeleine Albright and Mr. Clinton ordered

the FBI to stop photographing and fingerprinting Iranian wrestlers and cultural

delegations entering the U.S. because the Iranians were complaining about the

identification procedure. Of course they were complaining. It made it more

difficult for their intelligence agents and terrorist coordinators to infiltrate

into America. I was overruled by an "angry" president and Mr. Berger

who said the FBI was interfering with their rapprochement with Iran.

Finally, frustrated in my attempts to execute Mr. Clinton's "leave no

stone unturned" order, I called former president George H.W. Bush. I had

learned that he was about to meet Crown Prince Abdullah on another matter. After

fully briefing Mr. Bush on the impasse and faxing him the talking points that I

had now been working on for over two years, he personally asked the crown prince

to allow FBI agents to interview the detained bombers.

After his Saturday meeting with now-King Abdullah, Mr. Bush called me to say

that he made the request, and that the Saudis would be calling me. A few hours

later, Prince Bandar, then the Saudi ambassador to Washington, asked me to come

out to McLean, Va., on Monday to see Crown Prince Abdullah. When I met him with

Wyche Fowler, our Saudi ambassador, and FBI counterterrorism chief Dale Watson,

the crown prince was holding my talking points. He told me Mr. Bush had made the

request for the FBI, which he granted, and told Prince Bandar to instruct Nayef

to arrange for FBI agents to interview the prisoners.

Several weeks later, agents interviewed the co-conspirators. For the first

time since the 1996 attack, we obtained direct evidence of Iran's complicity.

What Mr. Clinton failed to do for three years was accomplished in minutes by his

predecessor. This was the breakthrough we had been waiting for, and the attorney

general and I immediately went to Mr. Berger with news of the Saudi prison

interviews.

Upon being advised that our investigation now had proof that Iran blew up

Khobar Towers, Mr. Berger's astounding response was: "Who knows about

this?" His next, and wrong, comment was: "That's just hearsay."

When I explained that under the Rules of Federal Evidence the detainees'

comments were indeed more than "hearsay," for the first time ever he

became interested--and alarmed--about the case. But this interest translated

into nothing more than Washington "damage control" meetings held out

of the fear that Congress, and ordinary Americans, would find out that Iran

murdered our soldiers. After those meetings, neither the president, nor anyone

else in the administration, was heard from again about Khobar.

Sadly, this fits into a larger pattern of U.S. governments sending the wrong

message to Tehran. Almost 13 years before Iran committed its terrorist act of

war against America at Khobar, it used its surrogates, the Lebanese Hezbollah,

to murder 241 Marines in their Beirut barracks. The U.S. response to that 1983

outrage was to pull our military forces out of the region. Such timidity was not

lost upon Tehran. As with Beirut, Tehran once again received loud and clear from

the U.S. its consistent message that there would be no price to pay for its acts

of war against America. As for the 19 dead warriors and their families, their

commander in chief had deserted them, leaving only the FBI to carry on the

fight.

The Khobar bombing case eventually led to indictments in 2001, thanks to the

personal leadership of President George W. Bush and Condoleezza Rice. But

justice has been a long time coming. Only so much can be done, after all, with

arrest warrants and judicial process. Bin Laden and his two separate pre-9/11

arrest warrants are a case in point.

Still, many stones remain unturned. It remains to be seen whether the Khobar

case and its fugitives will make it onto the list of America's demands in

"talks" with the Iranians. Or will we ultimately ignore justice and

buy a separate peace with our enemy?

Mr. Freeh was FBI director from 1993 through 2001.

Used with permission from OpinionJournal.com, a web site from Dow Jones & Company, Inc.